Science communication should shift from dissemination of knowledge to exchange of perspectives and collaborative inquiry in dialogue.

Science communication aiming to increase public acceptance of science is highly criticized; public worries need to be taken seriously and it needs to be acknowledged that the public has relevant knowledge for deciding on how to deal with scientific innovation. This means that in science communication, the focus is less on dissemination of scientific knowledge by experts and more on the exchange of perspectives and collaborative inquiry in dialogue. For scientists and other experts this means that their roles in science communication are changing. They no longer need to be neutral encyclopedias who educate the public. Instead, they need to reinvent their role and because of their previous expert status they will automatically be seen as role models in the new dynamics of dialogic science communication. This gives them a large responsibility, while scientists are not trained to enter in public dialogue. In their article ‘Experts in science communication: A shift from neutral encyclopedia to equal participant in dialogue’, Diewertje Houtman, Boy Vijlbrief & Sam Riedijk share their findings that indicate that scientists still adhere to an outdated science communication model. Scientists are trained to present information and discuss facts and evidence. So how can they unlearn these communication strategies unfit for dialogue and what should their new roles in science communication be?

During the past decades, public communication of science has undergone profound changes: from policy-driven to policy-informing, from promoting science to interpreting science, and from dissemination to interaction. These shifts in communication paradigms have an impact on what is expected from scientists who engage in public communication: they should be seen as fellow citizens rather than experts whose task is to increase scientific literacy of the lay public. Many scientists engage in science communication, because they see this as their responsibility toward society. Yet, a significant proportion of researchers still view public engagement as an activity of talking to rather than with the public. The highly criticized “deficit model” that sees the role of experts as educating the public to mitigate skepticism still persists.

Indeed, a survey we conducted among experts in training seems to corroborate the persistence of the deficit model even among younger scientists. Based on these results and our own experience with organizing public dialogues about human germline gene editing, we discuss the implications of this outdated science communication model and an alternative model of public engagement, that aims to align science with the needs and values of the public.

According to the deficit model, science skepticism is largely caused by a lack of knowledge and understanding. Accordingly, the role of scientists and other experts is to address this knowledge deficit and increase public understanding of science to increase public sympathy for and trust in science. This model accumulated criticism over time, because it largely ignores other factors than a lack of knowledge that can cause skepticism, as well as other types of knowledge that are crucial for understanding the role of science in society. Thus, science communication shifted from the deficit model to the dialogue model along with different recommendations on the role of experts. The dialogue model acknowledges that the public possesses important contextual knowledge, that there are other causes for skepticism, and that there are other forms of knowledge that influence public opinion. Experts should therefore engage in public communication of science with the aim of mutual learning rather than merely educating the public. Even though many experts might be hesitant to employ this new communication strategy, there are important reasons for doing so: Involving the public in decision‐making will generate trust in science; aligning expertise and public values has a positive impact on society; and introducing new and outsider perspectives contributes to well‐informed and reflective decision‐making.

A multidisciplinary stakeholder group of medical professionals, scientists, representatives of patient organizations, policy practitioners, government organizations, ethicists, communication specialists, and students gathered in June 2019 at a symposium called “Dialogue about human germline gene editing: how to?” organized by the Dutch Association for Community Genetics and Public Health Genomics (NACGG). During an interactive presentation by one of the authors (Diewertje Houtman), participants were asked “What are important conditions for a successful public dialogue about human germline gene editing?”. A significant number of responses focused on informing, educating, or explaining, which indicates that a still prominent perspective on science communication among experts is that it should counteract a perceived science literacy deficit.

Based on these responses, we started the DNA‐dialogue project with a tailored briefing for experts to draw their attention to important aspects of the dialogue approach. “Dialogue asks for an approach in which it is important to be aware of the following: we do not strive for debate, but for dialogue; not to convince, but to explore. […] During the dialogue, we would like to ask you to focus primarily on initiating and maintaining a safe environment to share thoughts, arguments, intuitions, hunches, or insights. Be an expert where necessary, or requested, but above all, engage in conversation with the other participants in the dialogue. As role models, you have a chance to embody mutual learning in the dialogue”. We are so used to inform, debate and defend […] that this has become our standard communication strategy with any audience.

However, even when we invited experts to leave their ivory tower and join an open dialogue with society, for some, if not most of them, this is just a one‐time experience and not likely to change their ingrained communication habits. We were therefore interested in investigating to what degree “experts” still adhere to the deficit model or to what degree they adopted communication habits in line with the dialogue model.

Between September 2020 and November 2020, we distributed a short questionnaire among students of the minor “Genetics in Society” in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, visitors of the 2020 Dutch Society of Human Genetics conference, and visitors of the German GfH‐Junior Akademie 2020, a meeting for young doctors and scientists in the field of human genetics. Their age ranged from 17 to 64 years, with a median of 36.5. Participants were at different stages of their career: The youngest was in the final year of high school, and the oldest had 38 years of experience working in the field of clinical research. Participants were working in or following education in clinical genetics, psychology, neurology, journalism, management, molecular biology, and clinical laboratory work.

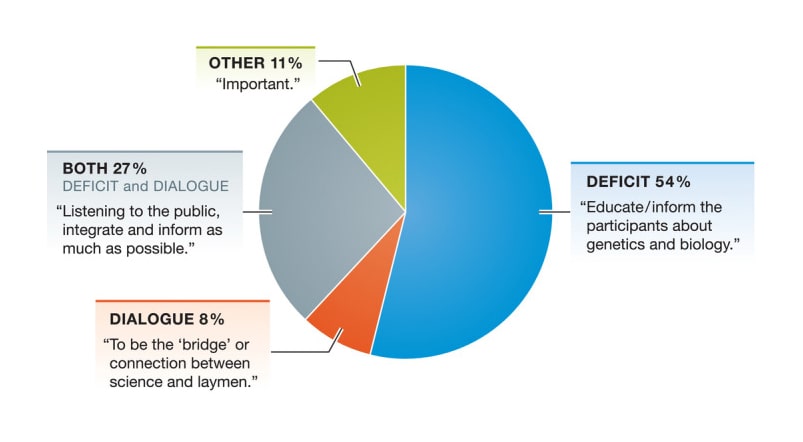

The question relevant for this article was “What do you think is the role of an expert in public dialogue?”. A total of 92 answers were assessed for dialogue characteristics (A: helping/supporting others in forming their opinion, B: increasing the inclusivity of dialogue, and C: listening or a combination of the aforementioned) and/or deficit characteristics (A: informing/educating the public, B: telling the public what is true and what is not, and C: aiming to increase public trust in science or a combination of the aforementioned). Interrater reliability was sufficient for both dialogue characteristics (κ = 0.758, P < 0.001) and deficit characteristics (κ = 0.812, P < 0.001). The results (image below) show that consistent with previous studies, there is still a significant proportion of experts at various phases of their career, of various ages and in various disciplines, who characterize their role in public dialogue in accordance with the deficit model (54%). Notably, there were only three people who explicitly stated that the role of experts in public dialogue includes listening, and none of the participants mentioned interaction or learning something themselves.

Science communication aiming to increase public acceptance of science is highly criticized; public worries need to be taken seriously and it needs to be acknowledged that the public has relevant knowledge for deciding on how to deal with scientific innovation. This means that in science communication, the focus is less on dissemination of scientific knowledge by experts and more on the exchange of perspectives and collaborative inquiry in dialogue. For scientists and other experts this means that their roles in science communication are changing. They no longer need to be neutral encyclopedias who educate the public. Instead, they need to reinvent their role and because of their previous expert status they will automatically be seen as role models in the new dynamics of dialogic science communication. This gives them a large responsibility, while scientists are not trained to enter in public dialogue. In their article ‘Experts in science communication: A shift from neutral encyclopedia to equal participant in dialogue’, Diewertje Houtman, Boy Vijlbrief & Sam Riedijk share their findings that indicate that scientists still adhere to an outdated science communication model. Scientists are trained to present information and discuss facts and evidence. So how can they unlearn these communication strategies unfit for dialogue and what should their new roles in science communication be?

During the past decades, public communication of science has undergone profound changes: from policy-driven to policy-informing, from promoting science to interpreting science, and from dissemination to interaction. These shifts in communication paradigms have an impact on what is expected from scientists who engage in public communication: they should be seen as fellow citizens rather than experts whose task is to increase scientific literacy of the lay public. Many scientists engage in science communication, because they see this as their responsibility toward society. Yet, a significant proportion of researchers still view public engagement as an activity of talking to rather than with the public. The highly criticized “deficit model” that sees the role of experts as educating the public to mitigate skepticism still persists.

Indeed, a survey we conducted among experts in training seems to corroborate the persistence of the deficit model even among younger scientists. Based on these results and our own experience with organizing public dialogues about human germline gene editing, we discuss the implications of this outdated science communication model and an alternative model of public engagement, that aims to align science with the needs and values of the public.

According to the deficit model, science skepticism is largely caused by a lack of knowledge and understanding. Accordingly, the role of scientists and other experts is to address this knowledge deficit and increase public understanding of science to increase public sympathy for and trust in science. This model accumulated criticism over time, because it largely ignores other factors than a lack of knowledge that can cause skepticism, as well as other types of knowledge that are crucial for understanding the role of science in society. Thus, science communication shifted from the deficit model to the dialogue model along with different recommendations on the role of experts. The dialogue model acknowledges that the public possesses important contextual knowledge, that there are other causes for skepticism, and that there are other forms of knowledge that influence public opinion. Experts should therefore engage in public communication of science with the aim of mutual learning rather than merely educating the public. Even though many experts might be hesitant to employ this new communication strategy, there are important reasons for doing so: Involving the public in decision‐making will generate trust in science; aligning expertise and public values has a positive impact on society; and introducing new and outsider perspectives contributes to well‐informed and reflective decision‐making.

A multidisciplinary stakeholder group of medical professionals, scientists, representatives of patient organizations, policy practitioners, government organizations, ethicists, communication specialists, and students gathered in June 2019 at a symposium called “Dialogue about human germline gene editing: how to?” organized by the Dutch Association for Community Genetics and Public Health Genomics (NACGG). During an interactive presentation by one of the authors (Diewertje Houtman), participants were asked “What are important conditions for a successful public dialogue about human germline gene editing?”. A significant number of responses focused on informing, educating, or explaining, which indicates that a still prominent perspective on science communication among experts is that it should counteract a perceived science literacy deficit.

Based on these responses, we started the DNA‐dialogue project with a tailored briefing for experts to draw their attention to important aspects of the dialogue approach. “Dialogue asks for an approach in which it is important to be aware of the following: we do not strive for debate, but for dialogue; not to convince, but to explore. […] During the dialogue, we would like to ask you to focus primarily on initiating and maintaining a safe environment to share thoughts, arguments, intuitions, hunches, or insights. Be an expert where necessary, or requested, but above all, engage in conversation with the other participants in the dialogue. As role models, you have a chance to embody mutual learning in the dialogue”. We are so used to inform, debate and defend […] that this has become our standard communication strategy with any audience.

However, even when we invited experts to leave their ivory tower and join an open dialogue with society, for some, if not most of them, this is just a one‐time experience and not likely to change their ingrained communication habits. We were therefore interested in investigating to what degree “experts” still adhere to the deficit model or to what degree they adopted communication habits in line with the dialogue model.

Between September 2020 and November 2020, we distributed a short questionnaire among students of the minor “Genetics in Society” in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, visitors of the 2020 Dutch Society of Human Genetics conference, and visitors of the German GfH‐Junior Akademie 2020, a meeting for young doctors and scientists in the field of human genetics. Their age ranged from 17 to 64 years, with a median of 36.5. Participants were at different stages of their career: The youngest was in the final year of high school, and the oldest had 38 years of experience working in the field of clinical research. Participants were working in or following education in clinical genetics, psychology, neurology, journalism, management, molecular biology, and clinical laboratory work.

The question relevant for this article was “What do you think is the role of an expert in public dialogue?”. A total of 92 answers were assessed for dialogue characteristics (A: helping/supporting others in forming their opinion, B: increasing the inclusivity of dialogue, and C: listening or a combination of the aforementioned) and/or deficit characteristics (A: informing/educating the public, B: telling the public what is true and what is not, and C: aiming to increase public trust in science or a combination of the aforementioned). Interrater reliability was sufficient for both dialogue characteristics (κ = 0.758, P < 0.001) and deficit characteristics (κ = 0.812, P < 0.001). The results (image below) show that consistent with previous studies, there is still a significant proportion of experts at various phases of their career, of various ages and in various disciplines, who characterize their role in public dialogue in accordance with the deficit model (54%). Notably, there were only three people who explicitly stated that the role of experts in public dialogue includes listening, and none of the participants mentioned interaction or learning something themselves.

Scientists are trained in the scientific method, and their communication training accordingly focuses on presenting and discussing facts and evidence. Before the DNA‐dialogue project, our team also fell back to the deficit model in engaging publics about gene editing in the human germline. We were merely presenting scientific knowledge, only to find out afterward that visitors understood even less about germline gene editing than they did before. We are so used to inform, debate, and defend—presenting at a conference, providing guest lectures, defending our PhD research, pitching research ideas, or leading competitive calls for funding—that this has become our standard communication strategy with any audience. This depersonalized and disconnected role is in sharp contrast with what the dialogue format requires. Dialogue allows experts to acknowledge their personal perspectives, needs and worries, and to open up to different types of knowledge, such as experiential or emotional knowledge. Experts in dialogue are individuals of flesh and blood, rather than algorithms. They aim to learn something and to connect, rather than push their own ideas forward.

Reincke et al (2020) state that experts in dialogue have a responsibility to share, listen and learn, and invest in relationships. We would like to emphasize that all participants in public dialogue essentially have these same responsibilities, as they are inherent to dialogue itself. However, experts may additionally have to unlearn their communication strategies and ignore the expectations of the role they should have in public dialogue. Placing experts on stage gives them a certain authority that may prevent others from taking part in the discourse. As absence of coercion is one of Habermas’s rules of discourse, most experts would probably need to step off the stage and let go of their role as “neutral encyclopedia”.

Houtman D, Vijlbrief B, Riedijk S. Experts in science communication: A shift from neutral encyclopedia to equal participant in dialogue. EMBO Rep. 2021 Aug 4;22(8):e52988. doi: 10.15252/embr.202152988. Epub 2021 Jul 16. PMID: 34269513; PMCID: PMC8344925.

Link to the publication including references

Photo: Chris van Koeverden

Scientists are trained in the scientific method, and their communication training accordingly focuses on presenting and discussing facts and evidence. Before the DNA‐dialogue project, our team also fell back to the deficit model in engaging publics about gene editing in the human germline. We were merely presenting scientific knowledge, only to find out afterward that visitors understood even less about germline gene editing than they did before. We are so used to inform, debate, and defend—presenting at a conference, providing guest lectures, defending our PhD research, pitching research ideas, or leading competitive calls for funding—that this has become our standard communication strategy with any audience. This depersonalized and disconnected role is in sharp contrast with what the dialogue format requires. Dialogue allows experts to acknowledge their personal perspectives, needs and worries, and to open up to different types of knowledge, such as experiential or emotional knowledge. Experts in dialogue are individuals of flesh and blood, rather than algorithms. They aim to learn something and to connect, rather than push their own ideas forward.

Reincke et al (2020) state that experts in dialogue have a responsibility to share, listen and learn, and invest in relationships. We would like to emphasize that all participants in public dialogue essentially have these same responsibilities, as they are inherent to dialogue itself. However, experts may additionally have to unlearn their communication strategies and ignore the expectations of the role they should have in public dialogue. Placing experts on stage gives them a certain authority that may prevent others from taking part in the discourse. As absence of coercion is one of Habermas’s rules of discourse, most experts would probably need to step off the stage and let go of their role as “neutral encyclopedia”.

Houtman D, Vijlbrief B, Riedijk S. Experts in science communication: A shift from neutral encyclopedia to equal participant in dialogue. EMBO Rep. 2021 Aug 4;22(8):e52988. doi: 10.15252/embr.202152988. Epub 2021 Jul 16. PMID: 34269513; PMCID: PMC8344925.

Link to the publication including references

Photo: Chris van Koeverden

© 2024 Symbiose All Rights Reserved.

© 2024 Symbiose All Rights Reserved.